It took two decades, but The Wire has finally reached its proper literary altitude. Feel free to unfasten your seat belt, recline your tray table and roam about about the cabin.

You see, this cabin is one of the few to showcase a television show that has entered the realm of high art. Elite club membership includes Hill Street Blues, The Sopranos and The Simpsons — stratospheric television achievements that elevated the medium that hoisted and foisted them as a newborns.

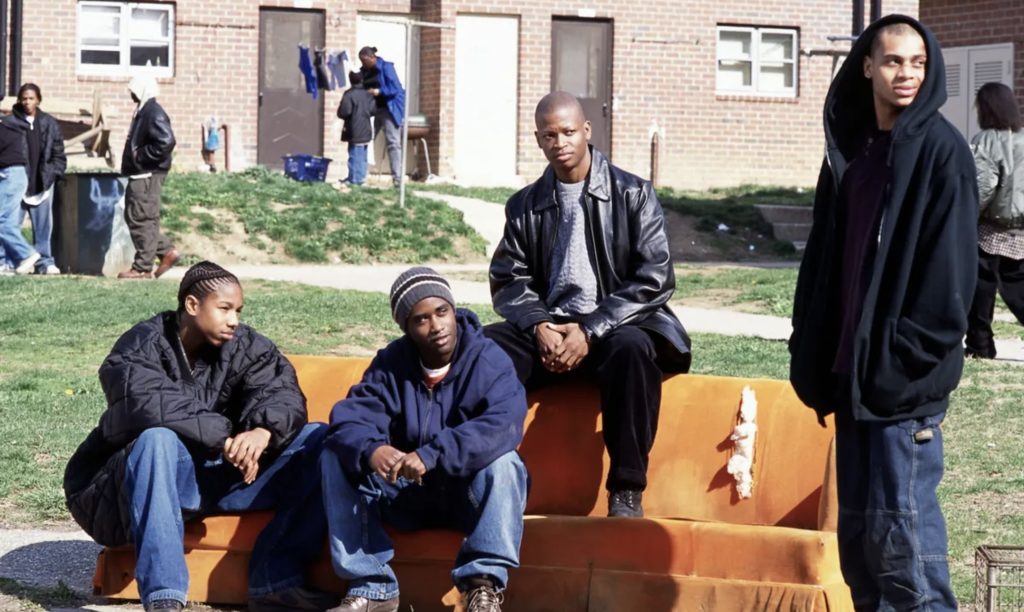

Maybe the epochal delay (the show is celebrating it’s 20-year anniversary this year) came from its unique DNA. The Wire may be America’s the first and only (intentional) five-sided television show. The police drama about life in the streets of Baltimore was divvied into five chapters of working America: crime; labor; politics; education; and journalism.That HBO even greenlit such a corporately-suspicious show is worth noting — along with the cold reality that no network, including HBO, would greenlight it today.

Which makes The Wire less a history lesson than an archeological find, a glimmer in a gold pan.

And one need look no further than Episode Two to find the treasure. Michael K. Williams played Omar Little, a scarred, poor gay gangbanger who served as a modern-day Robin Hood. Or Robbin’ ’Hood. Omar steals from gangs to feed his own, which is still victimized, but far less vicious. When Omar’s lover is ensnared, tortured and killed within “the game,” we become something more than spectators.

Consider the road The Wire could have taken, but did not. Any TV show could take that spark and stare at the candescent glow of a clever police procedural until disinterest reduced it to ember.

But creator David Simon, a former police reporter with the Baltimore Sun and author of Homicide, had no interest in flame — or navel — gazing. His octagonal intention was to examine the crumbling foundations beneath the feet of the city dwellers in Baltimore.

And thus America.

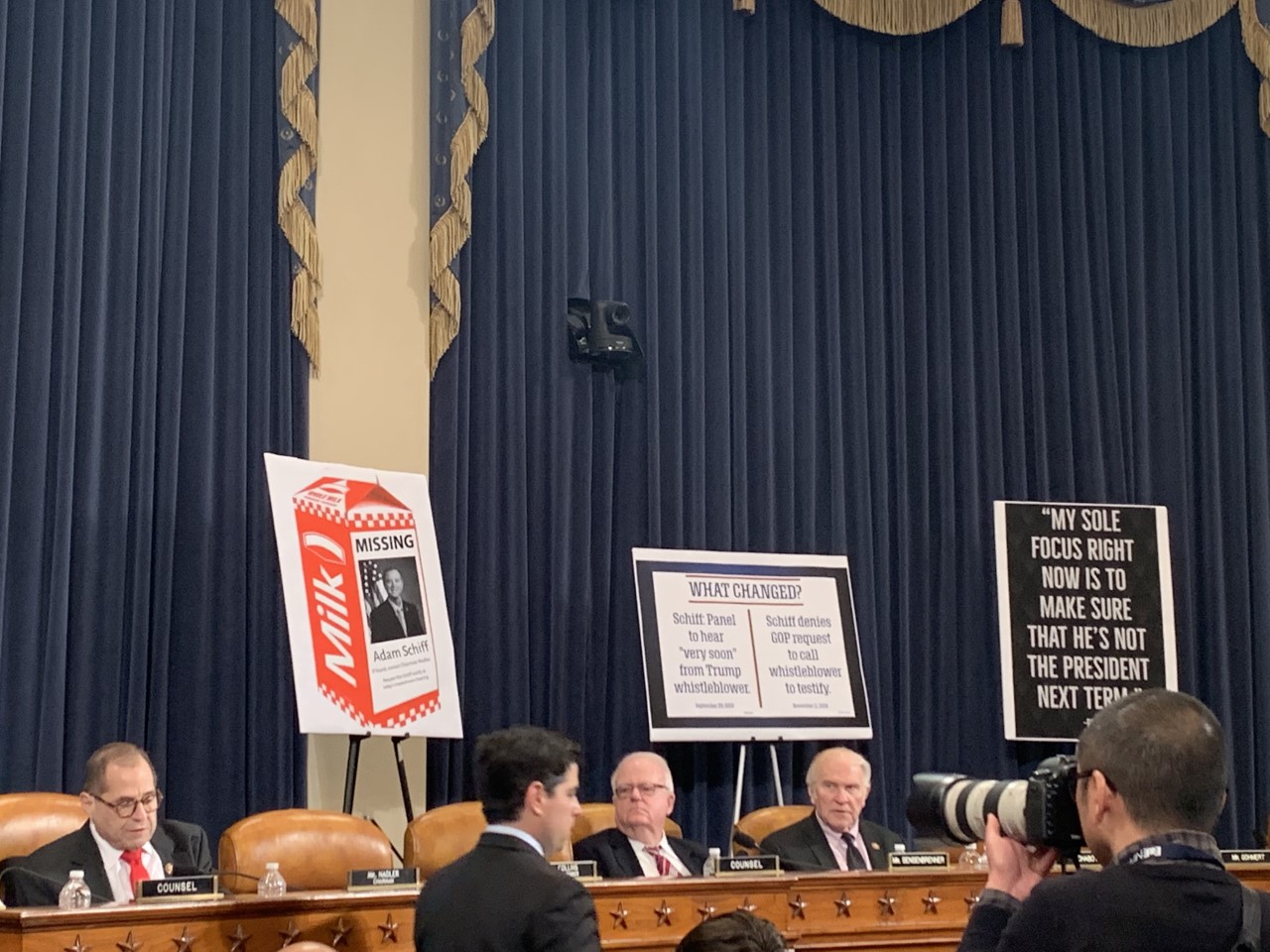

Colleges now teach The Wire and its themes as a course. President Obama called it the greatest television show of all-time. That it was nominated for only two Emmys — and won neither — effectively eliminating the venerated award as legitimate metric of quality.

Seasons One and Four are the show at its apex. Ironically, Simon’s look at journalism is the weakest chapter, largely because he views through the lens of a newspaper. Papers were already on life support by 2007, and the final season feels more like eulogy than observation.

And there’s no getting around the heavy lifting required to fully digest the show. I’ve watched the series four times now just to unpack its dense, tracer bullet dialogue. Simon filmed in Baltimore and used locals (some with felony records) to infuse scripts with current street and police slang. The language is so casually raw and the violence so blithely graphic, The Wire may have earned an NC-17 rating were it a film.

Fortunately, it’s not. Instead, it is a game-changer. The Wire may boast the longest list of anti-heroes ever committed to teleplay. From Omar to the alcoholic Detective McNulty to the psychopathic drug kingpin Marlo Stanfield, it’s often hard to tell who is antagonist and who is protagonist, which is Simon’s larger point.

And this may be The Wire’s: “The game” is an octagon, at least. And no one leaves uncut.