Evidentialism Slapfact: Killer whales are actually dolphins.

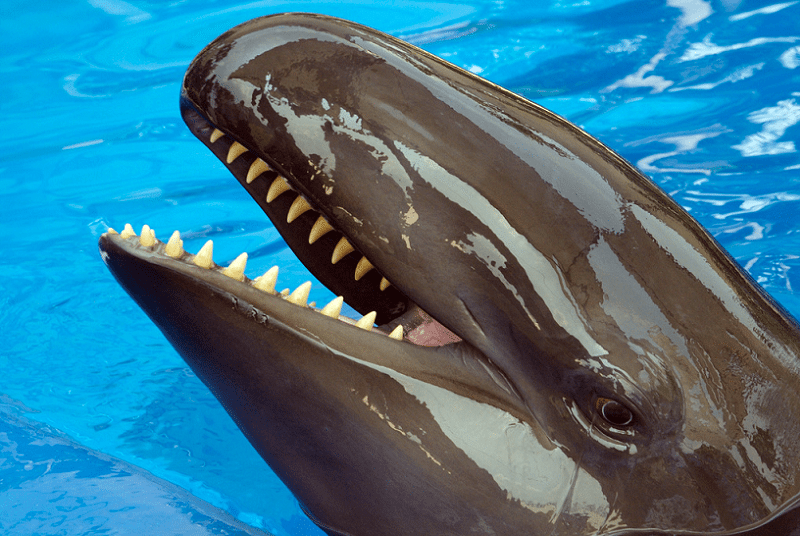

There are a few common misconceptions about killer whales, such as how they’re often seen as bloodthirsty creatures that hunt humans (they don’t — killer whale attacks are incredibly rare). But the biggest confusion about these black-and-white ocean dwellers is right in their name: They aren’t really whales. The Orcinus orca is actually the largest species in the Delphinidae (aka dolphin) family, weighing as much as 350 pounds at birth and growing up to 32 feet long during its 30- to 50-year life span. But in comparison to most whales — like the 100-foot blue whale, the largest animal on our planet — orcas are relatively small. Biologists also group killer whales with dolphins because of their aerodynamic body shape, which helps them reach speeds of up to 34 miles per hour, and their use of echolocation for hunting and navigation.

So why do we call them killer “whales”? The name stems from sailors of old, who witnessed the massive dolphins hunting whales (and other large marine mammals) together, and originally called them “whale killers.” Over time, the name was reordered, giving orcas a reputation as fierce and dangerous predators. These oceanic dolphins are clever hunters, known for beaching themselves to feast on seals and sea birds, and for working in pods to take down larger prey like great white sharks. But they’re also extremely social marine animals that spend their lives in matriarchal groups with as many as 40 members. Killer whales are so focused on community building that pods often host “greeting ceremonies” to meet members of other groups or welcome new babies, and hold aquatic funerals to mourn podmates. And the most reputation-busting research shows they might just like belly rubs.