The risk of making “based on true events” films is that sometimes the real events are more interesting than the fictional ones — and make for more entertaining moviegoing.

Take Man on Wire, an Oscar-winning documentary about a tight rope walker who crossed New York’s Twin Towers on a cable. The film was naturally followed by a big-budget feature starring Joseph Gordon Levitt. Alas, Levitt and co-stars could not match the mischievous humor of real-life walker Phillippe Petit and his cast of harmless hooligans, and the feature film plummeted to a flop that made only $10 million.

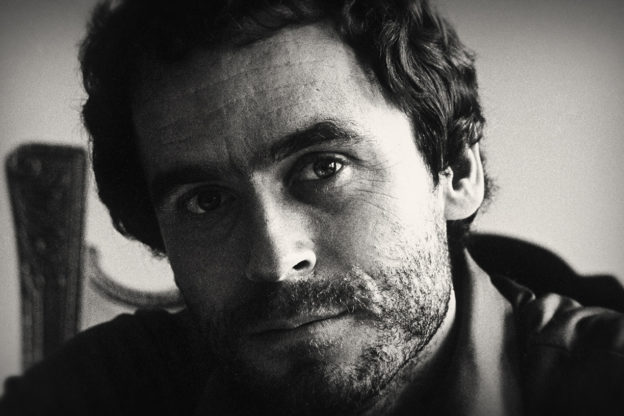

Netflix’s new film, Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, isn’t an equal disaster, but it comes up similarly short on the heels of the terrific Netflix documentary Conversation with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes. A serviceable-if-unspectacular thriller, Vile captures neither the horror of Bundy’s reign of terror, nor the charm Bundy used to lure victims, which numbered in the dozens.

It’s a strange shortcoming, given that both Bundy films shared the same director, Joe Berlinger (Paradise Lost, Brother’s Keeper). Documentary filmmaking is clearly his forte, and Vile ultimately feels detached enough from its characters to be a non-fiction flick, though there are some nice personal touches from the big-name cast, namely Zac Effron as the killer.

Still, Vile requires that you already know the story of America’s most notorious serial killer, because the movie does little to educate the viewer, let alone bring you into Bundy’s mind. Even the title is a bit misleading: Bundy may have been vile and wicked, but the movie is a largely bloodless examination of his cross-country killing spree, which left at least 30 women dead.

If anything, Vile glosses over the murders so briskly that it’s not until the final minutes of the nearly two-hour film that the savagery of Bundy’s acts become evident. And even then, you’re left with the sense you just watched an apt, if detached, Lifetime movie about a man’s hidden, murderous demons.

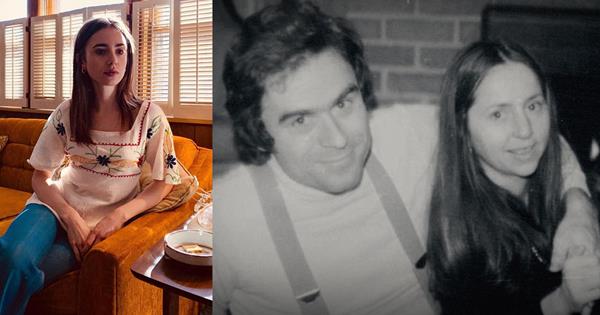

Instead, Vile concentrates on Liz Kendall (Lily Collins), Bundy’s ex-girlfriend and single mom who struggles to reconcile the man she knows with the headlines she’s reading. It’s a compelling portrait of falling in love with a monster, but Vile does a lackluster job of portraying just what a monster Bundy was. Despite Bundy strangling and raping his victims (and beheading at least one), Vile jettisons most of the violence for the headlines that followed.

If you don’t already know Bundy’s story, Berlinger’s carefully paced drama won’t spell it out for you; Bundy’s true nature stays largely below the surface. The deliberate pace of the narrative partly mirrors Liz’s own path from faith in her fiancé to creeping doubt. And Collins walks that line gracefully despite not being given much to work with, considering the movie is based on Kendall’s own memoir.

But it’s Efron’s movie. Alternately charming, belligerent, and incalculably shrewd, he captures both the shark-like charisma of Bundy and the deeply damaged man beneath. Problem is, news clips — some from Beringer’s previous documentary — suggest Bundy was more charming, more media savvy, even more handsome than the man playing him.

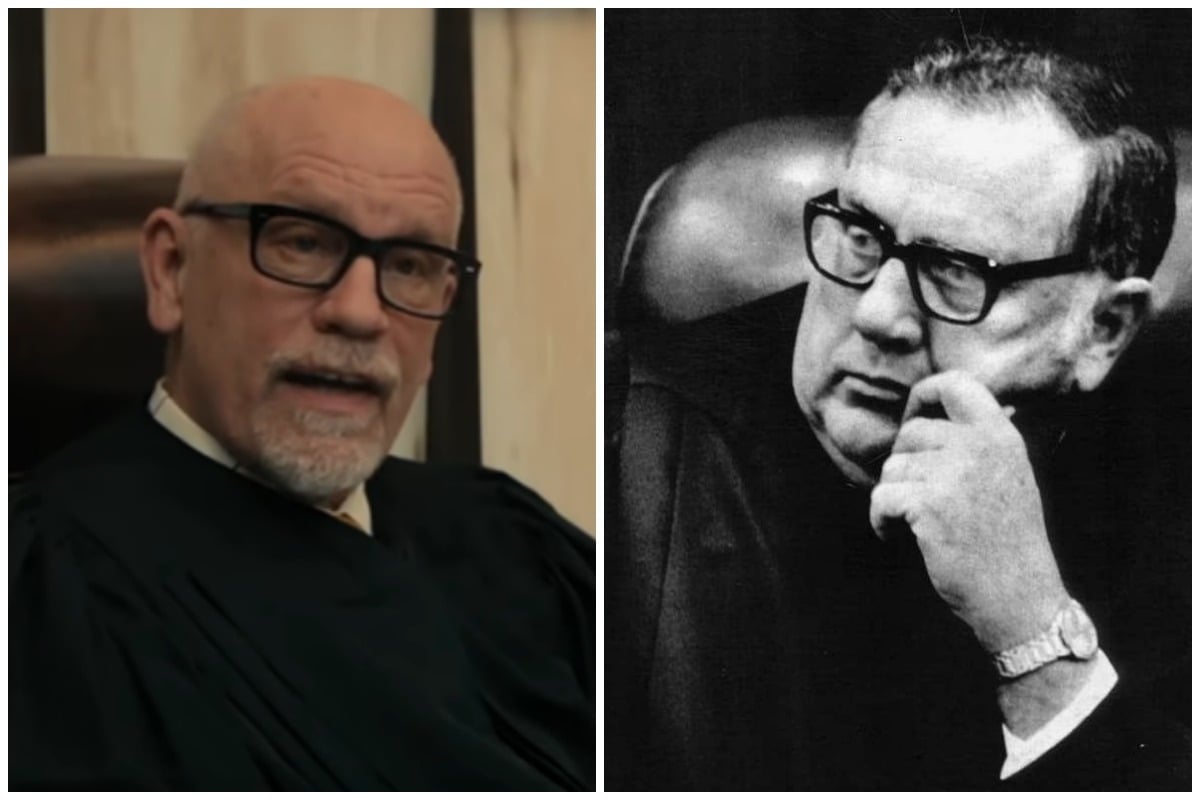

Vile‘s real strength is in its examination of a sociopath. Effron’s Bundy is a smooth talker whose lies are so effortless and convincing you think Bundy may believe them himself. And his rapport with Tallahassee judge Edward Cowart (John Malkovich), who finally renders judgement, is not only engaging, but nearly word-for-word accurate in its re-enactment of the nation’s first televised trial.

“You are skating on thin ice,” he tells Bundy at one point, “and ice does not last long in Florida.” He’s right, of course. But Vile leaves you wondering what made it crack.