I spent half my career as a police reporter. After watching Ronald Gene Simmons executed for killing 16 people over the Christmas holiday, I realized I wanted out of the death business.

So I took a beat as far-flung from crime as I could imagine: movie critic. In writing this review for a website, I was reminded why I left:

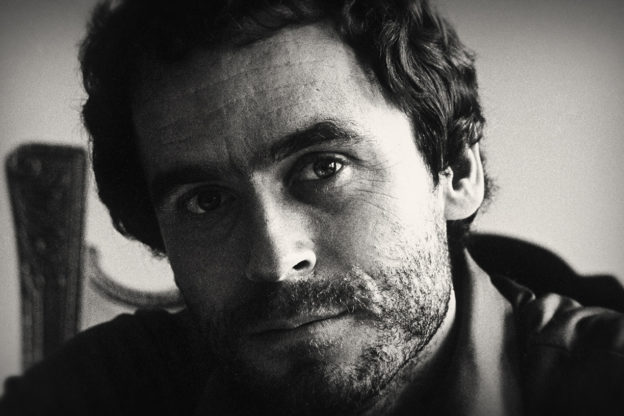

‘Ted Bundy was not your typical serial killer. Educated, telegenic and media-savvy, Bundy redefined how authorities hunted and captured murderers. He also forged a macabre template for Hollywood that persists to this day.

Fittingly, Netflix’s new film, Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, is not your typical crime documentary. Unlike the recent spate of real-life whodunnits, including Making a Murderer, The Innocent Man and The Staircase, Tapes is more concerned with documenting murder rather than questioning it.

While the murders are more than four decades old (the film marks the 30th anniversary of Bundy’s 1989 execution), it remains etched on America’s consciousness: Zac Efron will play Bundy in the film Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, which debuted at this year’s Sundance and will be released commercially later this year. And the documentary set Twitter so ablaze with panicked posts after its release the streaming service tweeted that audiences “not watch the movie alone,” though that may have simply been slick marketing.

Still, the documentary included several revelations about the case and demonstrated how Bundy’s killing spree forever heightened the nation’s fascination — and paranoia — surrounding random violence.

Directed by Oscar-winning filmmaker Joe Berlinger (Brother’s Keeper, the Paradise Lost trilogy), he begins the four-part series with a troubling, unexplained truth about the country: Serial killings became en vogue in the 1970’s. From Charles Manson to the Zodiac Killer to Son of Sam to John Wayne Gacy, the decade was essentially blood-stained with a series of random slayings that transfixed the country.

But none captured public attention like Bundy. Unlike the other murderers, whose homicides were contained in relatively small geographic regions, Bundy’s murders spanned seven states, beginning in Washington and ending in Florida. And none neared his body count; while Bundy confessed to 30 murders of women, police speculate he may have claimed more than 100 lives.

Even the story of how investigators and reporters obtained more than 80 hours of audiotape was something out of a movie. Until two days before he was sent to the electric chair, Bundy refused to admit to any killings. So frustrated questioners tried a different tack, asking him to explain how a killer might have committed such atrocities yet remain uncaught. Speaking in the third-person, Bundy obliged, apparently relishing reliving his elusive methods and two prison escapes.

Among the shows revelations:

Bundy road-tripped after his first escape. Bundy, who had a college degree in psychology, knew that local police jurisdictions communicated poorly. So after jumping out of a second-floor window during his kidnapping trial, he stole a car and began a 3,000-mile road trip, killing women in seven states. It took months for authorities to link the slayings.

Bite marks sealed his fate. Because police had no fingerprints and DNA analysis had not yet been invented, Bundy was convicted on meager evidence: bite marks on one victim — evidence now considered junk science. One of Bundy’s victims was bitten twice during her slaying. The marks matched Bundy’s crooked teeth, forensic experts testified.

Bundy was tried for murder while on death row. Florida prosecutors were so concerned Bundy might overturn his conviction on appeal, they prosecuted him on death row for the murder of 12-year-old Lynette Dawn Culver. He was found guilty based on a witness who saw Bundy force the girl into a van from her middle school.

Bundy started a family on death row. Bundy, who acted as his own defense lawyer, proposed to girlfriend Carol Ann Boone as she sat on the witness stand (prosecutors believe he thought it would make him appear sympathetic). She accepted and the couple, who surreptitiously copulated behind bars, conceived a daughter on death row.

Bundy inspired FBI profiling. Following Bundy’s arrest — along with the high-profile surge in serial killings — the FBI began collecting details of the slayings into a single database, and began training agents to look for similar traits. Bundy himself became a profiler, collecting news stories and sharing theories with agents who would visit him for counsel.

Berlinger sprinkles the show with other sensationalist details, including that Bundy later confessed to necrophilia and beheading some victims. The confessions, often recorded in whispers through prison Plexiglas, were an attempt by Bundy to “cleanse his soul,” the film explains.

But the true revelation of the series is how Bundy remains imprinted on our culture. He had groupies at his trials, young women who attempted to deliver love notes to him through his attorneys (all rejected). And the pop culture image we have of serial killers remains Bundy-esque: brilliant, cunning and eloquent, sometimes dashing. Think Hannibal Lecter, Dexter, American Psycho‘s Patrick Bateman, You‘s Joe Goldberg.

The most telling depiction, though, comes from Bundy himself, in the last words captured in Tapes:

“We want to be able to say we can identify these dangerous people. And the really scary thing is you can’t identify them. People don’t realize that there are potential killers among them. How could anyone live in a society where people they liked, loved, lived with, worked with, and admired could the next day turn out to be the most demonic people imaginable?” ‘