It must be Oscar time, because suddenly Hollywood’s credulity is in question. Again.

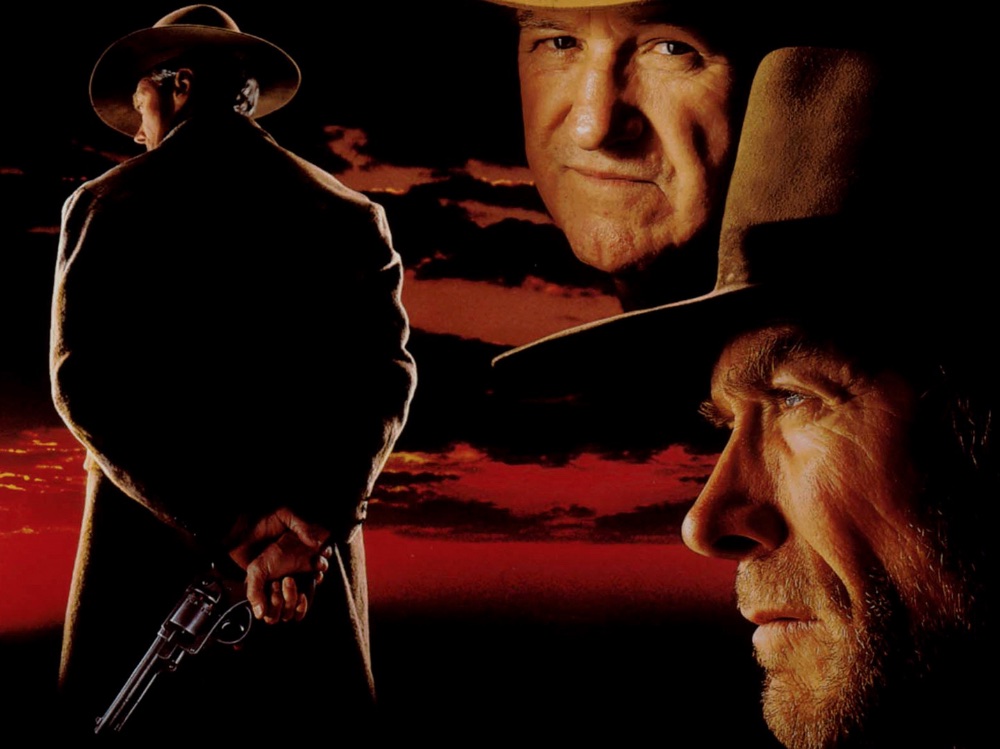

This is an old refrain the final months leading up to the Academy Awards, which are annually inundated with biopics and historical epics, all vying for statuettes. This year’s favorite accuracy arguments concern popes and the press. Clint Eastwood was pilloried for his attack on the media in his drama Richard Jewell, and Netflix’s Oscar hopeful The Two Popes earned the ridicule of some papal purists who considered the Fernando Meirelles film inaccurate and dumbed-down for commercial audience. (Full disclosure, I also railed about Jewell, though for personal reasons).

To my fellow film critics, I ask: Shouldn’t we be as diligent “truth squadding” movies the other eight months of the year? Either that, or accept Oscar fare as pure entertainment, as we do with, say, summer movies? To hold a film to a higher threshold of accuracy because of its release date is not only unfair to directors; it’s inaccurate for readers and viewers.

The truth is, in 15 years of movie reporting and reviewing, I have never interviewed a feature film director much concerned with getting the facts straight in any “based on a true story” (BOTS) film. Documentary film directors are a different lot (particularly Werner Herzog), though make no mistake: They edit footage with the same intention as their feature film counterparts — to tell a compelling story.

But from Chris Nolan (Dunkirk) to Martin Scorsese (Goodfellas) to Eastwood, details have always taken a backseat to drama. Without exception, directors promoting their BOTS films have told me that their jobs aren’t to teach history (if anything, studios consider that box office death). Instead, they say, their job is to accurately capture the tableau of emotions that spring from that history (directors love the word zeitgeist). Even Tom Hanks, who played the titular role in the much-maligned Somali pirate film Captain Phillips, told me he was drawn to the role because it captured the strains of living life at sea, not the subtleties.

That “capture-the-essence” approach isn’t likely to change anytime soon, particularly given the success of two films this weekend at the Golden Globes, 1917 and Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood. In both cases, the directors took on based-on-true stories, but with approaches starkly different from competing filmmakers.

In 1917, the fictional story of two World War I soldiers racing to prevent a suicide march, director Sam Mendes ended the movie with a postscript that said the film was dedicated to his grandfather, WWI vet Alfred Hubert Mendes, who told his family that story innumerable times.

Quentin Tarantino, who directed Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, went even further. He loves to wreak havoc with historical accounts. In Inglorious Basterds, he ends the film with the heroes killing Hitler in an eruption of bullets and flames.

He did something similar in Hollywood, taking the real-life horror of the Charles Manson slayings and giving viewers the visceral ending they would have preferred (and get in most other straight-up features).

Their strategy worked like a Swiss watch. The Hollywood Foreign Press Association showered both movies in awards. 1917 won Golden Globe for best drama and director, while Hollywood took best comedy or musical and best screenplay for Tarantino. Popes, The Irishman and Jewell were all but forgotten.

Even holding a BOTS film’s feet to the fact-fire seems silly. What effective entertainment, on some level, isn’t based on a truth? Just as all music draws from notes that have been played before, so too are the reductive themes in film. Star Wars is essentially a father-son story. Casablanca is about love during wartime. You can’t copyright feelings.

Hollywood executives even go out of their way to point out a film’s factual failings — as long as it’s from another studio. Harvey Weinstein was renown for knocking the veracity of other studios’ BOTS movies. I can’t count how many publicists whispered under the breath when I asked about a competing biopic or historical portrait, ‘I hear it’s not a bad movie. Too bad it’s not true.’

So if Hollywood isn’t going to change its ways, perhaps we need to. Both Bohemian Rhapsody and Rocketma, for example, are rife with inaccuracies in portrayals of their subjects, Freddie Mercury and Elton John, respectively. But Rhapsody, which came out during Oscar season 2018, drew much more rigorous examination than Rocketman, released this summer. To scrutinize one but not the other implies one has accuracy issues, becoming in itself a journalistic inaccuracy.

Perhaps the answer is to treat BOTS films the way we treat political rallies, which are eerily similar: both take liberties with facts to win favor with a largely dim-witted crowd that won’t bother to look up facts on their own.

So the job falls to us to watch “true stories” with a boulder-sized grain of salt and the assumption they will require some fact-checking. Who knows? It may even improve our film reviews, a sidebar comparing fact to fiction.

It’s time we decide whether we’re going to treat these films as reporters or audience members. We need to regard BOTS films for what they really are: not a kiddie pool of facts, but a diving board into deeper knowledge. Hollywood films are just the divining rods.

Movie critics already have fallen out of the fact-finding business. Maybe it’s time we work some muscle memory.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/63565045/film_review_the_15_17_to_paris_74069523.0.jpg)