Clint Eastwood’s latest film, Richard Jewell, opened this weekend to $5 million, a thumbs-up from more than 70% of the nation’s critics and with Oscar whispers circling the Warner Bros. flick. I gave it four out of five stars for my outlet.

I would have given it five stars, but there was a ginormous caveat in the way: Clint took an unwarranted shot at an old colleague of mine. Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter Kathy Scruggs and I worked the police beat at the AJC, though I had moved to another paper by the time of the Centennial bombing during the 1996 Olympic Games.

Scruggs, who died in 2001, was the primary reporter in the AJC‘s bomb coverage. She also broke the story that the FBI was looking at Jewell as the primary suspect. And when Eric Rudolph, an anti-abortion extremist and member of the Army of God sect, confessed to the bombing, Scruggs took it on the chin from competing outlets for her aggressive, over-eager zeal to get a scoop. Which was true. Kathy had the bite force of a rabid pit bull when she got hold of a story.

But, to hear Eastwood tell it (on film), Scruggs took it on the chin, literally. The film accuses Scruggs of sleeping with an FBI agent to get the story. The AJC has protested its portrayal, which is irony perhaps at its purest. And Warner Bros did what the AJC did 2 1/2 decades ago: It told the protesters to go pound salt.

But the paper was right. Eastwood screwed this up.

I say that with all the hesitancy I can muster. In truth, I have spoken to Eastwood more often than I talked to Scruggs, and consider myself a fully biased fan of his work. But Eastwood must have had an acutely unpleasant run-in with the press of late, because he took a hatchet to media the way Jack Torrance opened doors.

Eastwood got virtually everything wrong about reporters in Jewell, which is odd, since we really were the antagonists in this story. We did swarm. We did leap. We did jump the gun.

But for some reason, the 89-year-old director needed a villain incarnate, and created one with Scruggs. He directed Wilde to play the reporter as if she were Cruella de Vil with a notepad. In the film, Scruggs flips off fellow reporters, weeps at press conferences and basks in the standing ovation she receives for initially breaking the Jewell story.

Bullshit bullshit bullshit. The woman portrayed in Jewell is not Kathy Scruggs.

I can’t speak to the specific allegation Eastwood made. But I can say with no degree of uncertainty that his notion of a newsroom is antiquated and, worse, waaaay off. Reporters don’t give standing ovations. We can barely tuck in our shirts. We don’t even applaud when colleagues win a Pulitzer Prize. And no reporter screams in delight when a story runs above the fold in banner font. We hold our breaths and pray we don’t need to run a correction.

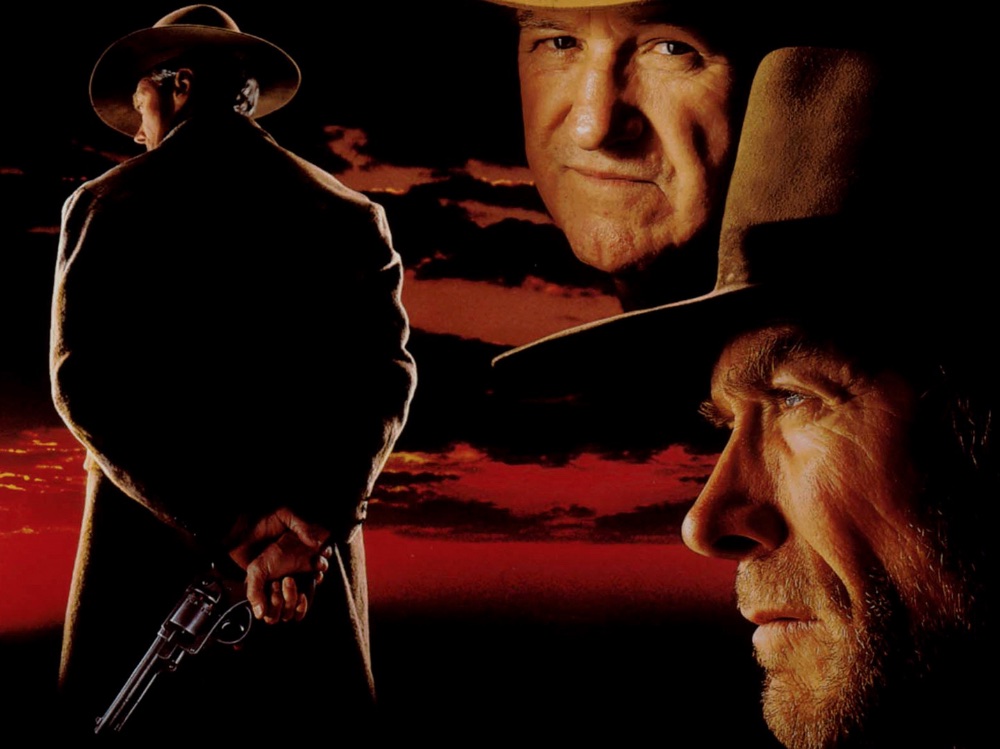

The inaccuracy is a jarring failure on Eastwood’s part. He won a best director Oscar on the back of historical research by screenwriter David Peeples for the Western Unforgiven. Peeples was also nominated for an Academy Award, though he didn’t win.

Maybe it was studio pressure. Maybe it was Eastwood’s well-publicized conservative political leanings that prompted him to take a shot at the media. Maybe he clashed with one of us on a red carpet (where we are at the zenith of our assholeness).

But to take a shot at a dead woman? Come on, Clint. That’s like shooting the guy in the black hat in the back.

More puzzling was that the filmmaker already had a believable villain in us. Throughout Jewell, reporters camp out in front of the suspect’s home, follow him wherever he drives and badger even Jewell’s mother in the feeding frenzy. When we amass, bad shit happens.

Alas, that wasn’t sufficient for Jewell.

I still remain a fan of the work of both Scruggs and Eastwood. One of the highlights of my career was to have an interview included in a collection of stories about the director.

So I will bid an RIP to Kathy and a best-wishes to Clint come Oscar season. I hope the movie does well. I will do my best to forgive it.