Pity poor James McGill.

He’s got a brilliant, condescending older brother who undermines his career dreams. He’s got such a penchant for scoundrels he becomes known as ‘Slippin’ Jimmy’ in the neighborhood for his staged injuries. He has the Albuquerque branch of the Mexican drug cartel miffed.

And now he has to carry on the legacy of one of the greatest television shows of all-time, Breaking Bad.

Better Call Saul, which launched its second season this month, stands as a marked improvement over its smart-but-sporadic freshman year. Two episodes in, the series already has recovered some of the dark humor and violent tension that defined Vince Gilligan’s landmark preceding show.

Saul Goodman (Jimmy changed his name to match his motto: ‘S’all good, man.’) now has a love interest. A company car and his own digs. He’s even smoothing out the relationship with soon-to-be hired gun Mike Ehrmantraut.

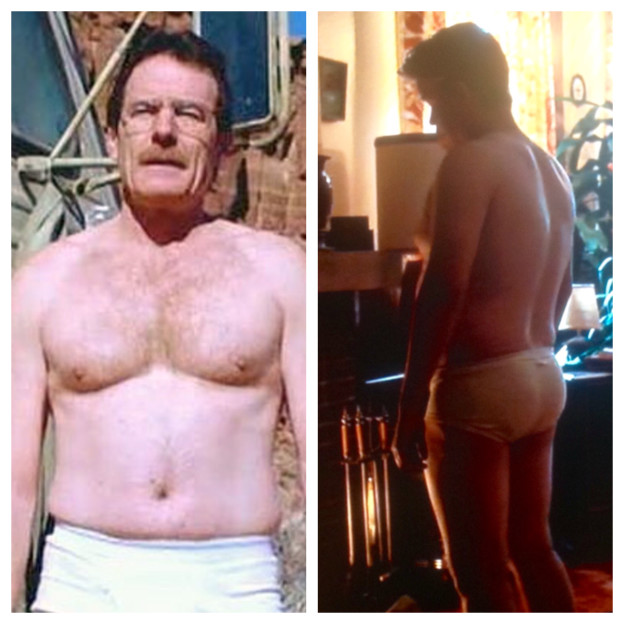

Of course, that puts Saul — and creators Gilligan and co-creator Peter Gould — in something of a pickle. As the chronological predecessor to Breaking Bad, Better Call Saul must, eventually, return its hero to the place we first saw him: In Breaking Bad climes, as a pretty sleazy Yellow Pages injury attorney.

Consider how Saul was first described by Jesse Pinkman in Season 2, Episode 8 of Breaking Bad: When you’re up against the wall, “you don’t want a criminal lawyer. You want a criminal lawyer.”

And while he was great comic relief, Saul also was, in truth, a racist and chauvinist. He openly propositioned his secretary Francesca (“You’re killing me with that booty”) and confided in Walter the reason he changed his name: “My real name’s McGill. The Jew thing I just do for the homeboys. They all want a pipe-hitting member of the tribe, so to speak.”

The Breaking Bad Saul even sassed the feds. In the same episode, he trades barbs with DEA macho man Hank Schrader, who offered an unsolicited review of Saul’s daytime TV commercials. “I’ve seen better acting in an epileptic whorehouse,” Hank taunted.

“Is that the one your mom works at?” Saul snapped back. “She still offering the two-for-one discount?” Saul is decidedly gentler in his own series, and Gilligan and Gould would appear to have wedged themselves into a creative corner.

But Gilligan takes to pickles like a kosher dill. He is the first to admit he likes to write his characters into near-inescapable peril — then have them pull Houdini-esque escapes. Gilligan said he knew, for instance, that he wanted to end Season 2 of Breaking Bad with a plane crash, even though the series had been as landlocked as a dehydrated scorpion. So he wrote the season finale first, then retrofitted the story arc to include an airline disaster.

Shades of those darker grays are surfacing in Saul. Just as Walt slowly circled the drain into villainy in Breaking Bad, Saul appears headed for a fate that will change his law-office nickname from Charlie Hustle to Charlie Hustler. Just how dark a fate? In Gilligan’s hands, you’re almost scared to ask.

Still, Saul deserves credit for understatedly fixing what Hollywood movie studios still can’t: creating tension in a prequel. There’s a certain lack of suspense in an opening chapter: After all, your hero has to survive an origins story if chapter two is already written (and a hit). Gilligan and Gould circumvented that by making Better Caul Saul both flashback and prequel, leaving us to fret over his ultimate fate.

Of course, Saul the man still has a ways to go before he becomes a lovable lowlife, just as Saul the show faces its own challenges turning sinister: Mike continues to look older than he did in the “sequel” show, and capturing any of Breaking Bad‘s bleak lightning in a bottle would seem an impossible appeal.

But in the courtroom of television drama, even a shadow of Breaking Bad is a convincing argument. And in Gilligan’s and Gould’s hands, s’all good.