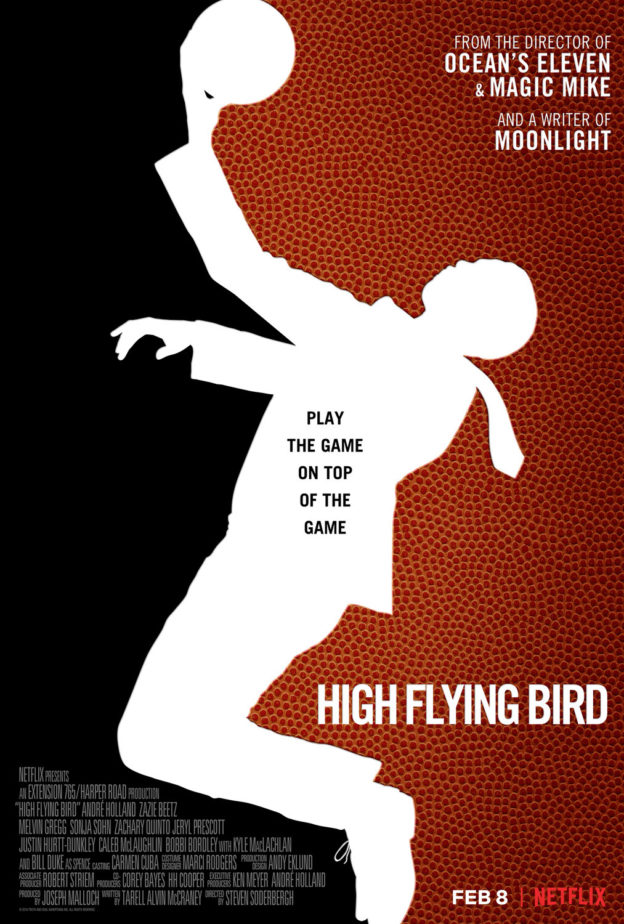

High Flying Bird fittingly resembles a no-look pass in basketball: unexpected, deftly maneuvered, and usually resulting in a score. And while Steven Soderbergh’s latest movie accomplishes most of the achievements of the flashy pass — including a score — it isn’t quite a slam dunk.

There’s no denying the basketball drama was unexpected, on a couple levels. First, it proved reports of Soderbergh’s retirement were greatly exaggerated, primarily by Soderbergh. He announced to New York Magazine in 2013 that he was done with film because of Hollywood’s shabby treatment of directors and emphasis on profit.

“Just to be clear, I won’t be directing ‘cinema,’ for lack of a better word,” he told the magazine in January 2013. “But I still plan to direct — theater stuff, and I’d do a TV series if something great were to come along.”

Soderbergh was either bluffing or trying to build buzz for projects, because he’s been anything but idle the last six years. He directed Logan Lucky in 2017, 27 episodes of The Knick and Mosaic for TV, and two movies in the past two years, last year’s Unsane and Friday’s Bird, which premiered on Netflix. But grant him this: He is rebelling somewhat against the film industry. Both Unsane and Bird were shot using iPhones.

And while his filming gadgets of choice feel (and occasionally look) gimmicky, there’s no denying Soderbergh’s mastery of the medium. Topical, tautly-written and showcasing the director’s love of disruption, this story of the economic battle between NBA owners and players marks his best work in years.

Written by Oscar-winning Moonlight screenwriter Tarell Alvin McCraney, Bird is set during 2011’s protracted NBA lockout, where players and owners battled for eight months over the pay and say-so they deserved in America’s most merchandise-friendly sport. The film pointedly notes that neither football nor baseball lure kids to Footlocker to buy cleats, let alone help propel rap and hip hop verses.

The film follows African-American sports agent Ray Burke (Moonlight‘s André Holland) as he wheels and deals while being torn over his own ambition and the concerns of the players he represents, including Erick Scott (Melvin Gregg), a hot-headed, hotshot No. 1 draft pick. Ray’s career is on the line and his bank account nearly empty as the lockout wears on, and Bird underscores how the world of LeBron James and Steph Curry are not the world of the NBA’s rank-and-file players, many of whom feel the financial pinch of missing a paycheck and trying to support family, friends and hangers-on. Bird opens with a tense lunch conversation between Ray and Erick, both of whom need the lockout to end soon. Erick, we learn, has already had to get spending money from a loan shark, while Ray has to pay for lunch with cash, as his corporate credit card is maxed out.

Bird follows Ray for 72 hours as he tries to end the stalemate by staging a series of unsanctioned basketball games that will pressure management into a fairer settlement. All while he manages the egos and aspirations of players, up-and-coming agents like Sam (Zazie Beetz) and fat-cat team owners embodied by the oily New York owner David (Kyle MacLachlan).

The film’s strongest moments come in its unexpected twists. Despite being a basketball drama, there’s no buzzer beater finish; Bird doesn’t even show a single game played. And it does a concise job of explaining how the league became a billion-dollar industry overlaid by racial tensions as white owners saw the profitability and marketability of the Harlem Globetrotters. Especially nice are the black-and-white interviews with real NBA stars Karl-Anthony Towns, Donovan Mitchell and Reggie Jackson, who lend the movie a sense of authenticity with their personal stories of adjusting to the NBA.

Bird also has a nice sense of the realities of today’s game, from players’ viral videos to their social media presence to the often overbearing pressure of players’ parents angling to manage their kids’ affairs. There’s an especially canny moment when Ray contemplates the profitability of airing unsanctioned games on Hulu and Netflix (the latter being the movie’s distributing studio).

Where Bird falls out of rhythm is in Soderbergh’s reliance on Aaron Sorkin-esque dialogue. Every player, coach, agent and exec speak so quickly and smoothly it can feel like you’re watching a play (McCraney is and remains a playwright). The lighting often feels too muted or stark, just as you’d expect on a phone video. And while the exploitative plantation mentality of pro basketball is a worthy and necessary point, the abundant slavery references can make Bird sound heavy-handed and repetitive.

But credit Soderbergh for not falling into sports movie tropes. While not a cinematic blowout, Bird manages to bring out solid performances of its roster.