When thrown correctly, the knuckleball is the hardest pitch to hit in baseball.

Apparently, it defies most laws of motion. While every other pitch in the human arsenal — fastball, curve, slider, change up, etc. — relies on spin to give a ball movement, a knuckleball is thrown with none, allowing gravity and physics to make it dip, lift, curve, whatever nature decides. You essentially push it over the plate. Pro catchers hate it; it is so deceptive and dodgy, catchers can look like bigger fools than batters trying to track one.

I learned this in yet another documentary I caught (damn you, ESPN) that, it turns out, really wasn’t about baseball. Or even sports.

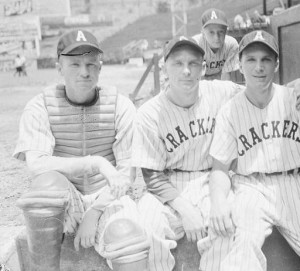

The talking heads were lamenting the dearth of knuckleballers, who once dominated the big leagues (my uncle Leonard, a former pro pitcher with the Georgia Crackers, had a good one, I’m told).  The toss is so difficult that less than a half dozen pitchers still practice it, and requires so much finger dexterity that a split nail can send a pitcher to the Injured Reserve List.

The toss is so difficult that less than a half dozen pitchers still practice it, and requires so much finger dexterity that a split nail can send a pitcher to the Injured Reserve List.

But it’s ego, not skill, that killed the knuckleball, the analysts said. Today’s sport (if not all modern competition) is defined by force, not finesse, and today’s Little Leaguers want to blaze 98 mph fastballs. A good knuckleball travels about 60 mph and takes, literally, years of practice and patience.

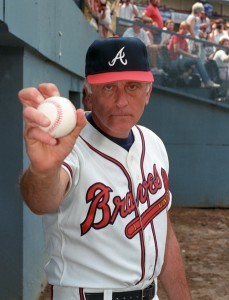

The film interviewed a few famed knucklers, from Phil Niekro to Tim Wakefield, diminutive men who said they turned to the pitch when they realized they didn’t have cannons for arms.

So I looked up their careers. Wakefield pitched for 24 years, Niekro for 23 (until he was 48, an octogenarian in the MLB).

But it was R.A. Dickey’s story that convinced me the knuckleball is The Everyman Pitch, the go-to backup when age and health and hope are on the wane.

Dickey was a flamethrower at the University of Tennessee, a right-hander deigned The Next Big Thing. The Texas Rangers came calling. He insured his whip for $1 million.

But during a routine examination, doctors discovered that Dickey lacked a particular ligament in his arm, a birth defect they said would end his career prematurely. Texas rescinded the contract, replacing it with a one-year deal for the league minimum, $75,000 a year.

Dickey weighed cashing in on the insurance, though it would mean he contractually could never pitch again.

Instead, he decided to rest his fate on the pitch his father taught him in their Nashville backyard (Dickey says his dad threw knuckleballs so that the boy, ever-hyper with a glove, would wear out faster chasing them). He took the contract and bounced around the minor leagues. He slept in a rental car and phoned his wife (his 7th grade sweetheart) and four kids with game updates. For a decade, no team would offer him a multi-year deal, fearing that his health and age would succumb before his abilities.

But in 2010, at age 34, he landed with the New York Mets, where he was to be used for occasional relief duties.

Instead, he won 11 games. Sportswriters noticed. Hitters noticed. And fans — many of them old enough to remember when the Mets didn’t suck — began turning out.  In droves, with signs and chants and ‘attaboys’ as word of the journeyman’s odyssey spread.

In droves, with signs and chants and ‘attaboys’ as word of the journeyman’s odyssey spread.

And in 2011, the Mets offered him his first real contract, worth $37 million over five years. He bought the family (now a brood of five) a house in upstate New York. His wife a new car. The kids college trust funds.

The next year, he won 20 games, was elected to his first All-Star Game, won the Sporting News Pitcher of the Year Award, and became the first knuckleballer to ever win the Cy Young Award, the sport’s greatest pitching honor.

He is still hurling today, still relying on fingernails and physics and fate to strike out men bigger, stronger, faster — but never more patient or crafty. Asked about his unlikely success, Dickey gave an answer that, ultimately, was unrelated to stitches and peanuts and Cracker Jack.

“At some point, I had to decide to be true to what I knew inside,” he said. “That’s the thing about knuckleballs. You try to bring your best to the mound. But in the end, all you can do is throw the best pitch you’ve got, and see what it does in the world.”