Warning: spoilers and curves ahead

Mad Men was a profound show that flirted with a profound ending.

Instead, it chose a mildly ambiguous one. Which, by today’s standards, could qualify as profound.

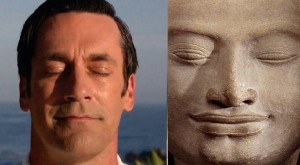

But you couldn’t help but feel unfulfilled by the final chapter of the eight-year odyssey of Don Draper. The slick adman and reality escape artist was grinning like Buddha at show’s final scene, having come up with the ad pitch of all ad pitches: the I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke jingle.

Much hay has been made over the finale (sorry, Don, there’s no escaping your farm roots), which has been heaped with praise for neatly wrapping characters’ story lines and giving viewers the Matt Weiner sendoff we never got in The Sopranos. And no finale ruins the legacy of a series (look at M*A*S*H*, or Seinfeld, or any series finale).

But just as Tony Soprano’s final scene remains under-appreciated (in a television first, the viewer got whacked), Mad Men‘s final episode has attracted fawning like a gleaming blue Cadillac; it’s over-praise, and fleeting.

The problem may have been in the show’s genius concept: How the appearance of happiness often trumps the appreciation of it.

And for eight years, Weiner and writers took an unflinching look at that inner-conflict, creating one of the most complex anti-heroes in television history in Draper (played with deft narcissism by Jon Hamm). His was a protagonist capable of great nobility — and unspeakable trespasses.

Which is why Mad Men shouldn’t have ended on a punchline, however brilliant.

And there’s no arguing the cleverness of the joke. The real ad was conceived by the minds at McCann-Erickson in 1971. Draper was working for McCann-Erickson on the show, which also had reached 1971. And Mad Men can perhaps boast a television first: the only series to end on a commercial. Normally they’re followed by one.

But the real ambiguity of Mad Men is not in the finale’s contents, but its intent. What are we to make of Don’s last smile? That it takes a human touch to be a good salesman? That work can’t equal happiness? Or can it? That, if you run fast enough from your past, you can start over?

Perhaps Weiner telegraphed the ending in the opening graphics of the series eight years ago. Every week, the show began on a familiar graphic: A suited man, plummeting from a skyscraper hued by womens’ silhouettes, only to land neatly on a couch, still coiffed, cigarette perfectly in place. Maybe that was the setup to the punchline.

We may never know, which may be the point. Or perhaps the show ended on a punchline that Weiner had in mind years before the show’s final bow (he said often that he knew how he wanted the series to end).

Either way, there was no shaking the sense that we’d just seen a great sales pitch. And like most ads, the promise is far more grand than the payoff.