There’s no reason the Karate Kid franchise should still work — which is exactly why it does.

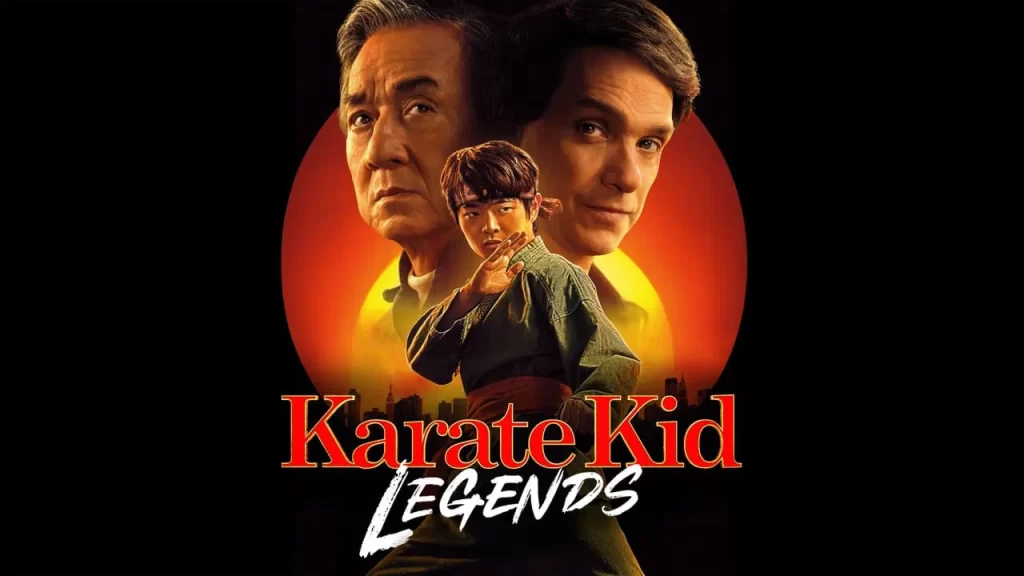

The original dropped in 1984. It’s 2025. And yet, here comes another installment: Karate Kid: Legends, hitting theaters May 30. Ralph Macchio is back. So is Jackie Chan. And now, they’re in the same movie. Two generations of martial arts mentors, teaming up to train a new kid — Li Fong, played by American Born Chinese breakout Ben Wang — in a reboot that pulls from both timelines. It shouldn’t work. But it always does.

That’s the trick with Karate Kid: it evolves just enough to stay young. It bends but never breaks. The core is still there — humility, resilience, the kind of honor that comes from losing first and learning fast.

The franchise never relied on capes or cosmic stakes. No gods. No aliens. Just bruised egos, bloody knuckles, and broken homes.

That’s why it sticks. It’s not about fighting. It’s about earning your ground. Even Cobra Kai, the Netflix spinoff that could’ve gone full parody, played it straight. It gave old characters new depth, flipped the moral compass, and pulled in a new generation without losing the old.

The franchise isn’t afraid to change faces. Hilary Swank took the lead in 1994. Jaden Smith rebooted it in 2010. Now it’s Ben Wang’s turn.

The baton passes without ceremony. No multiverse monologue. Just a new kid, a new sensei, and the same fight to matter. That’s what makes it real.

Financially, it still kicks. The 2010 version made $359 million worldwide. The franchise total sits over $430 million — not counting Cobra Kai’s streaming dominance. Even now, with Chan reportedly dislocating his shoulder on set at age 70, the films keep selling stakes as something earned, not animated.

The secret’s simple: there’s always a kid who doesn’t belong. Always a bully. Always a mentor with too much past and just enough patience. The dojo changes, the accents change, the year changes. But the lesson never does.

Balance. Timing. Respect.

Everything else is just choreography.