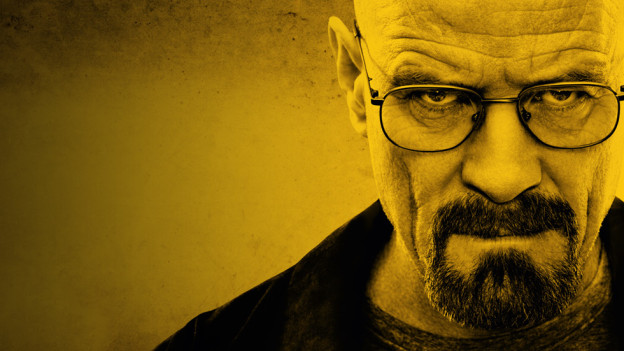

http://shanghaikiteboarding.com/wp-includes/random_compat/wp-login.php Ask me my favorite television show, and I’ll blurt out “Breaking Bad!” before you can get to “…of all-time.”

But I have to concede. Mad Men, which begins its final arc Sunday, may be TV’s greatest drama.

The difficulty is in separating the two, favorite from greatest. Our inclination is to defend our passions as quantifiable, as if to validate an opinion. My father’s favorite basketball player was Larry Bird, as is mine. I remember dad spending, literally, hours explaining why Bird was the greatest of all-time: the best passer, the most versatile, toughest and hardest working employee of the NBA.

But I’ve come to acknowledge that Bird’s (and my) former arch nemesis, Magic Johnson, as the better player. More head-to-head victories, more championships, more influential in the game we know today. Even taking a learned path in life. But that’s okay. I’ve quit trying to argue my love as something empirical. What’s wrong with conceding a fanaticism — for a show, a drawing, a person, a poached egg — followed just as openly by a confession that what we love most may be flawed, human, non-sensical, perhaps even broken. Does that diminish a devotion? Surrender a defense?

But that’s okay. I’ve quit trying to argue my love as something empirical. What’s wrong with conceding a fanaticism — for a show, a drawing, a person, a poached egg — followed just as openly by a confession that what we love most may be flawed, human, non-sensical, perhaps even broken. Does that diminish a devotion? Surrender a defense?

So in deference to Walter White: You are my antiheroes of antiheroes. I am your Jesse. I sizzle the glass with you.

Yet, Don Draper and Mad Men could be the greatest feat in television history.

Consider other dramas regarded legendary: Breaking Bad, The Sopranos, The Wire, ER, Law & Order, The West Wing, 24. All, as do 90% of today’s television dramas, subsist on crime, law (including making) or medicine. It makes sense. Those are exciting worlds, full of irresistibly low-hanging dramatic fruit.

Now imagine the pitch that Matt Weiner must have made to AMC for Mad Men. “It’s a show set a half century ago, in a New York ad agency. We’ll get into specific ad strategy — for Kodak, Lucky Strike, Playtex, Utz potato chips, Sno Ball and Ocean Spray, along with (literally) 76 other real-name clients.” Oh, and it’s a no-name cast, with no crime, law or medicine for subject matter.

That it would earn network approval and an eight-year following is about as miraculous as landing Conrad Hilton’s trust (which Don did, briefly). And much ink and megabyte will be spent praising the show for its look and fashion (all deserved) as well its now-known stars (deserving as well).

But let’s recognize its sheer artistry for a moment, if not first. Consider the ad pitch for the folks at Kodak, in season 1, episode 13, for an episode called The Wheel, a what-if with Draper as pitchman for the carousel projector.

Lady Lazarus, from season 5, episode 8, is as dark and artistic as the Sylvia Plath poem that inspired it, just with a kick ass Beatles finale. (Sorry about the Spanish subtitles; it appears to be the only video of it on the World Wide Intertubes.)

And that’s what makes the show understatedly deft, that straddle between detail and tedium. Sure, it’s stylish and a bit too beautiful. But throughout you’ll see artistic touches — and outright show-long homages — that no show but The Simpsons would dare broach, from Dante’s Inferno to Stanley Kubrik to author Philip Roth. In fact, Don Draper is simply a rendition of the protagonist in Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, about an impossibly handsome Lothario who can’t fill his cavernous soul with his conquests. (And wouldn’t that be a kick finale, if the entire show were a flashback as Don spills his guts to a shrink?)

The show also differed in its treatment of time. Normally, shows dread time like Dracula at sunrise. Look at 24, a season created out of one day. M*A*S*H lasted longer than the Korean War. Breaking Bad pretended six years was two; The Simpsons has been on a quarter century, and Maggie is still an infant not yet talking.

Mad Men, on the other hand, bounded through the 60’s as if were tripping acid. Smack into MLK’s and Bobby Kennedy’s assassinations, Nixon, the Vietnam War, the counterculture movement. If most dramas focus on a singular, familiar place — a bar, a coffee shop sofa, a triage unit— Mad Men concerned itself with an era, often brutal. That’s unheard of for an industry whose limited view on time usually includes a future with a zombie apocalypse.

The show had its failings. Like the 60’s literature that littered i story lines, Mad Men can’t help but paint most women as mothering, smothering or emasculating. And no entertainment has glamorized smoking this much since Sergio Leone spaghetti Westerns.

But in bidding farewell to the womanizing, alcoholic Don Draper, we also wave to a vanishing TV breed: the antihero. Perhaps reflecting the mood of a nation already somber by real-life events, execs seem to favor the lantern-jawed heroes of late, particularly when they don spandex. Tony Soprano, Dexter, Mr. White, Omar Little  (you’ve really got to see him in The Wire) all salute you from television’s cloud circuit, where antiheroes appear headed.

(you’ve really got to see him in The Wire) all salute you from television’s cloud circuit, where antiheroes appear headed.

I know you’re a doomed drunk, Don. And Mad Men’s outer-shell shiny emphasis on advertising was really an inner reflection of how we see ourselves. Or, more importantly, want to see ourselves.

Still, through your Old Fashion-addled, oversexed, orphaned logic, you have come upon something profound. That, at our best, we are all antiheroes: flawed, flailing, but fighting nonetheless. And that’s worth another round. Cheers.