Deadline.

That’s the engine that drives September 5, a tense, disciplined film about the Munich Olympics hostage crisis—and the scramble inside an American newsroom to cover it in real time.

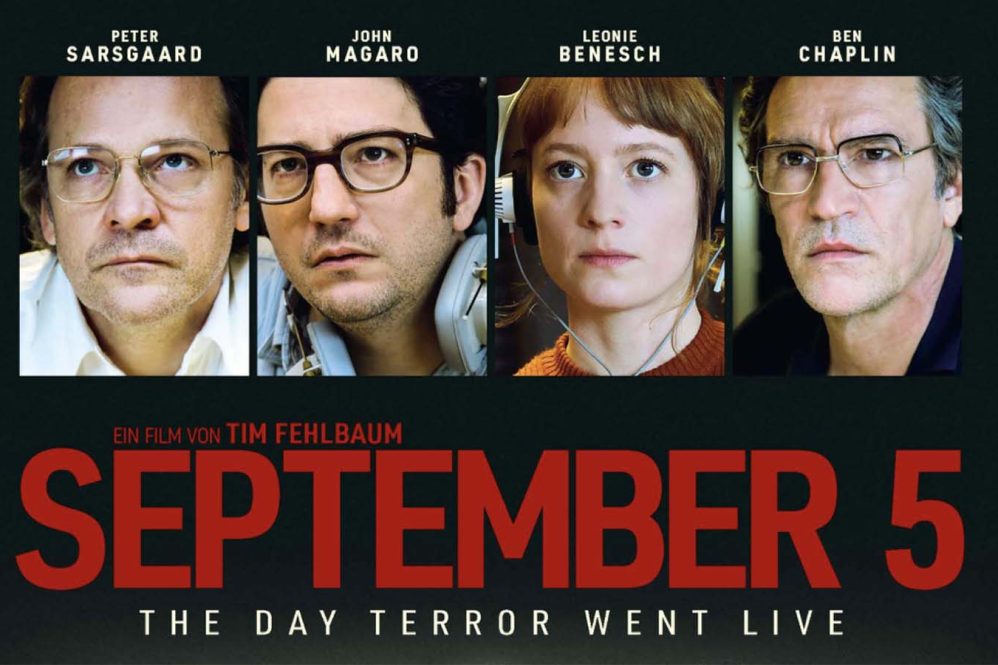

Directed by Tim Fehlbaum, the movie never leaves its chosen frame: the ABC Sports control room in Munich. Geoffrey Mason (John Magaro), an experienced producer, finds himself reporting on a terrorist attack, not a sporting event. Alongside him: network president Roone Arledge (Peter Sarsgaard), operations chief Marvin Bader (Ben Chaplin), and translator Marianne Gebhardt (Leonie Benesch).

The decision to keep the film anchored inside the newsroom is a smart one. There are no cutaways to politicians, no staged shots of the gunmen. The tension builds through headset chatter, garbled wire reports, and a dawning realization that no one—not the broadcasters, not the authorities—knows what’s actually happening.

Historically, September 5 holds its ground. The filmmakers drew from ABC archives and consulted surviving staffers.

The infamous false report that the hostages had been rescued—a mistake broadcast to millions—happened exactly as depicted. The pressure on the network to “get something on the air” is also drawn from the record. Where the film condenses or imagines, it does so in service of tone, not distortion.

The parallels to All the President’s Men and Network are inevitable, but September 5 charts its own course. It is less about institutional power than professional panic. It is not about triumph, nor satire. It’s about uncertainty, and how newsrooms operate when no one knows what is true.

The cast serves the material. Magaro plays Mason as a man whose calm is cracking. Sarsgaard’s Arledge is more calculating. And Benesch gives the film its conscience, translating not just words, but the mounting dread in the room.

September 5 does not glorify journalism. It shows it for what it often is in moments of crisis: a flawed, human effort to catch up to a world already spinning out of control.