Trípoli (Part of an occasional series.)

The Black Stallion is bookend-ed with two of Hollywood’s favorite tropes: the shipwreck and the horse race.

What happens in between, however, is anything but cliched. The 1979 film, produced by Francis Ford Coppola, is nothing short of magic, a profound adaptation of a children’s story that became arguably one of the first children’s art films in modern Hollywood.

Several fine movies have followed in that narrow niche, including Wall-E, The Iron Giant and Where the Wild Things Are.

But those films had the luxury of computer wizardry. What you see in The Black Stallion is a novice director teaming with a novice cinematographer who filmed everything they stumbled across on the Mediterranean beaches of Sardinia, Italy.

And what a trek! They capture un-digitized rainbows, un-pixelated sunsets and unabashed animal tricks, including swimming horses and striking cobras. The first half of the film, which includes 28 minutes without a word of dialogue, is simply art projected on a screen.

Based on Walter Farley’s bestselling book series of the 1940’s, The Black Stallion movie contains some of the most impressive nature scenes committed to film. That they reside in a feature film makes Stallion a literal visual fairy tale.

Consider two scenes in particular. In one, Alec (played by 12-year-old Kelly Reno, a Colorado-born cattle ranchers’ son who’d never acted a day in his life) feeds”The Black” a leaf of seaweed to earn its trust — and eventual love. In a long tracking shot, Reno beckons the Arabian horse so close to his face the horse could have easily bitten Reno’s nose off.

In another, Alec awakens one day early in his odyssey to a cobra inches from his face. Both remain near motionless, cobra hooded and hissing, until The Black arrives to stomp out the threat. Reno is among real animals, and was separated from the cobra simply by a pane of glass. It is one of the most intense scenes ever in a children’s film, yet Stallion would still be freighted with a dreaded G-rating.

Despite Coppola’s name and sway, The Black Stallion would not see the same storybook ending as The Black. The film sat for two years as studio heads bickered over a marketing strategy — or whether to market at all.

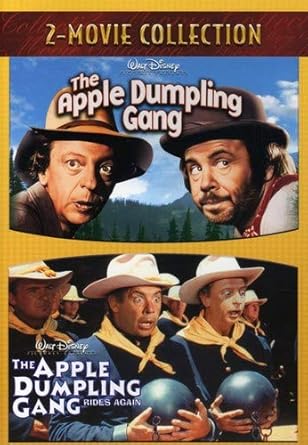

Despite some very adult themes, Stallion was saddled (sorry) with a G-rating that was tantamount to a death sentence at the time. Before computers made it relevant, the G-rated landscape was relegated to goofy live-action (The Apple Dumpling Gang, Escape to Witch Mountain) or traditional animation and puppetry (Charlie Brown, The Muppets). Dumplings may be simple, but they’re marketable.

And consider Stallion‘s competition for thoughtful adults in 1979, which saw the premieres of Apocalypse Now, Alien and Kramer vs. Kramer, among others.

Not that the film lagged commercially: It cost about $3 million to make, and took in almost $38 million at the box office (enough to warrant an awful sequel). But its artistry — from scenery to soundtrack — would not be fully recognized until years later. It was recently featured on the Turner Classic Movies network.

Stallion is the the perfect launch for Deja Viewed in particular and pandemic viewing in general. It’s part silent, all poetic, and is in no rush to get anywhere. Kind of like us.

And, regardless of how trying the pandemic is on our lives, The Black Stallion puts quarantine living in context. At least we’re not waking up with cobras.