There’s a scene early in Lake George when Don (Shea Whigham), a weary ex-con assigned to off a mobster’s girlfriend, squints through the grime of a windshield that hasn’t been cleaned in years.

The camera holds long enough for you to wonder whether he’s even trying to see, or if he just prefers his world this way—filtered, fractured, and deliberately dirty. It’s one of the many small, deliberate touches in Jeffrey Reiner’s Lake George that sets the film apart from your typical crime thriller.

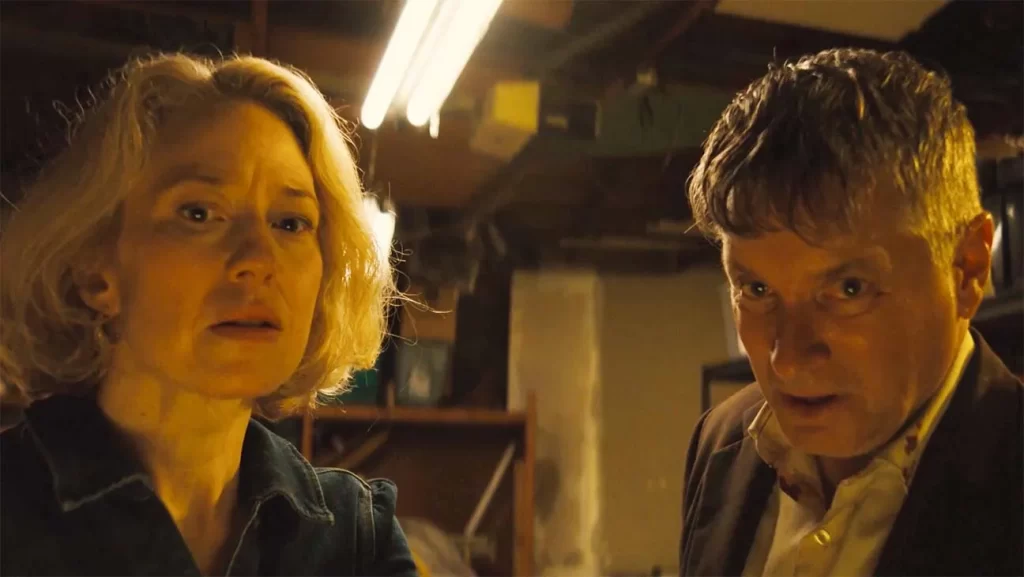

The setup is familiar: Don, fresh out of prison and riddled with a deep moral ambivalence, is sent to kill Phyllis (Carrie Coon), the whip-smart, world-weary moll of his boss.

What unfolds, though, is something grittier, slower, and more textured than a simple hit-gone-wrong. There’s violence, sure. There’s betrayal and paranoia.

But Reiner seems more interested in what happens between those beats: the way a character lights a cigarette with his off-hand because the dominant one is in a sling; the way Don half-limps down motel stairs, suggesting an injury we’ll never quite get explained; or the way no one ever bothers to clean a damn window in this world.

Those dirty windshields serve as more than atmosphere. They’re metaphor, mood, even mirror. Reiner shoots many scenes from inside cars, looking out through smudges and streaks, as if to suggest that clarity—of thought, of purpose, of truth—is perpetually just out of reach.

It’s a subtle choice, and one most films wouldn’t linger on, but here, it becomes almost a character in itself: the haze through which these people view each other and themselves.

Whigham is outstanding as Don, delivering a performance that’s all restraint and regret. He plays the role like a man who’s seen the worst parts of himself and is still figuring out if he deserves to be alive.

Coon matches him beat for beat, giving Phyllis a cunning softness that keeps you guessing which side she’s really on. The chemistry between them doesn’t sizzle so much as smolder—two people too damaged for flirtation, but drawn to each other’s wounds.

The pacing is deliberate—some might say slow—but Reiner earns it by layering his film with tension and atmosphere rather than plot twists. You don’t watch Lake George to find out what happens next; you watch to sit in its murky moral ambiguity, to appreciate the stillness between its bursts of violence.

This isn’t a movie for everyone. It resists easy resolution and offers little catharsis, particularly the finale.

But for those willing to watch through the dirt, Lake George offers a beautifully grimy view of redemption—uncertain, fogged over, and worth squinting at.