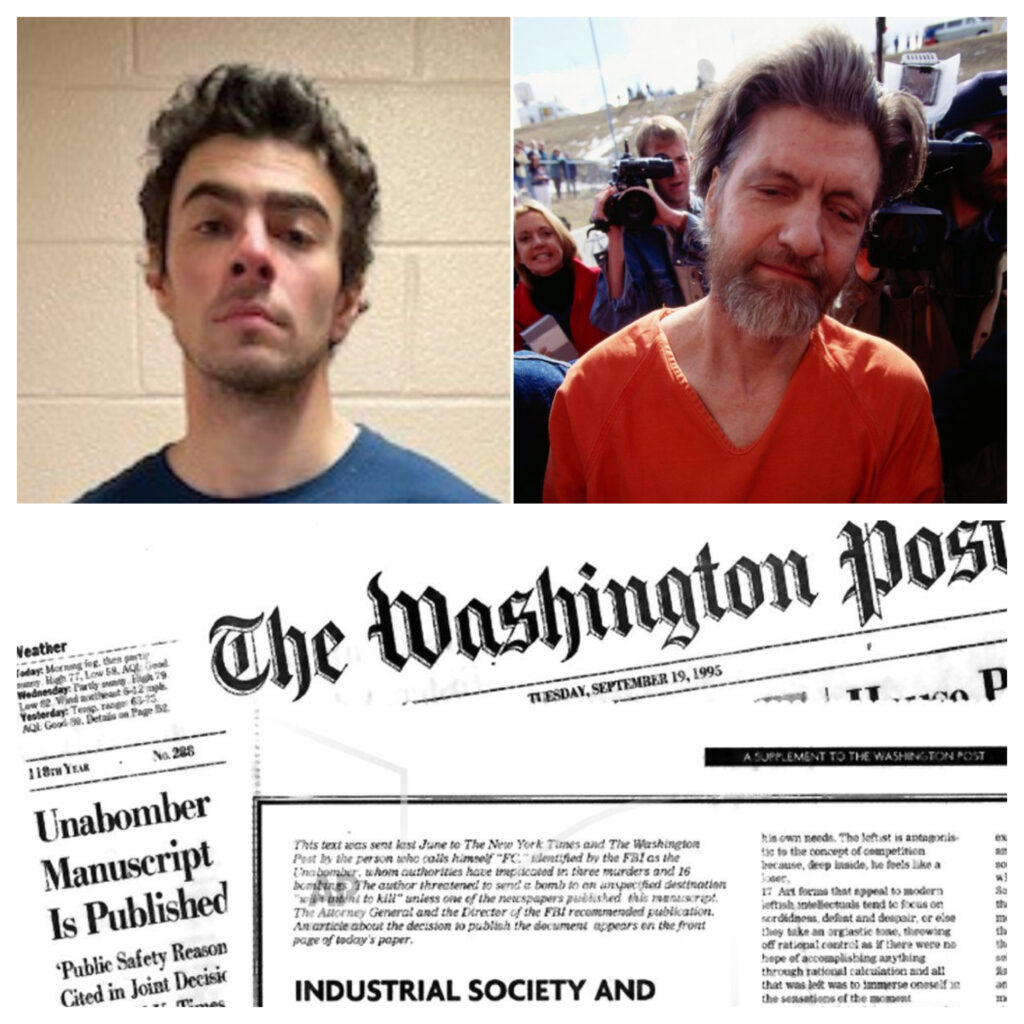

Cururupu I used to work at The Washington Post. I was there when Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, sent his manifesto to the Post and The New York Times. The decision to publish it was a mistake.

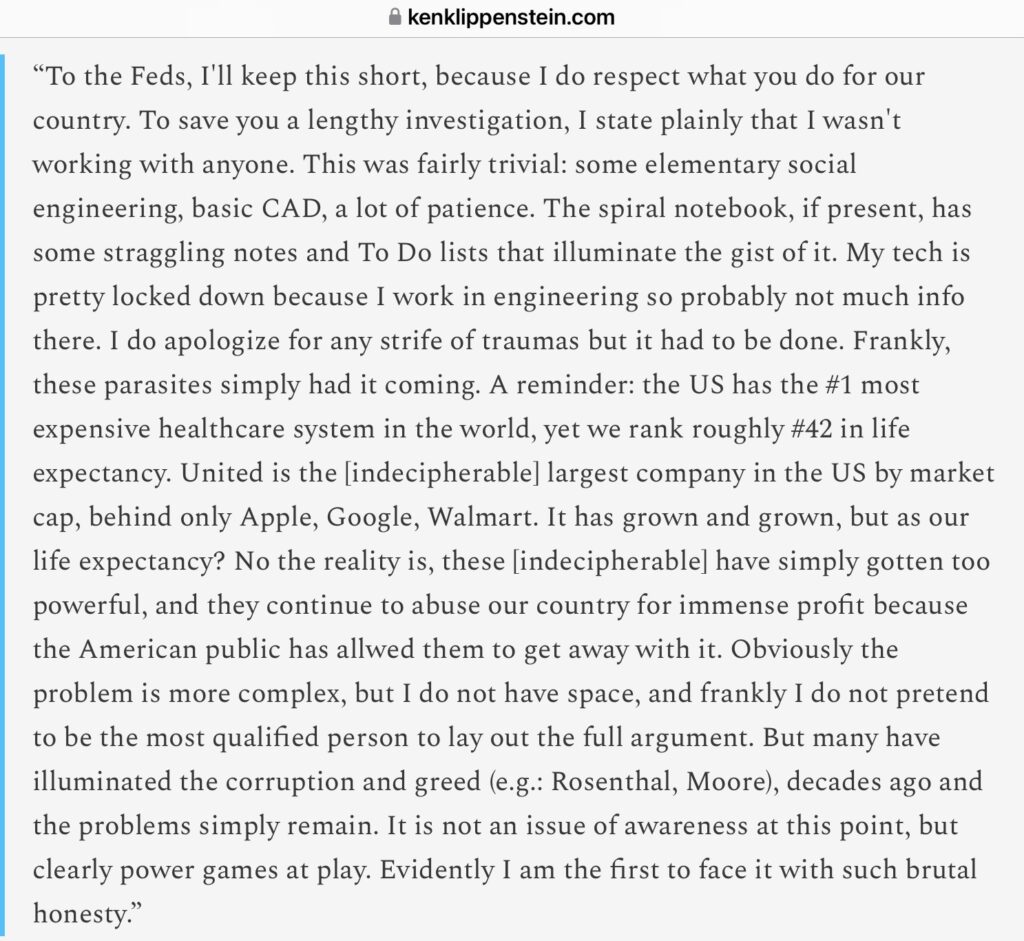

uvularly Now, decades later, I’m watching The Post make a different, but equally flawed, decision with Luigi Mangione’s manifesto. Mangione sent his 262-word note to several outlets. The Post obtained it. But they didn’t run it. Instead, they selectively quoted from it, releasing only the parts that aligned with the narrative law enforcement wanted to push.

Why? Because this is what The Post does now. The publication that once prided itself on holding the powerful accountable has become an adjunct of law enforcement.

They’ll never say it outright, of course. They’ll cite ethics, public safety, or journalistic discretion. But I know better. I was there when it started.

I was a cop reporter then in 1995, when Kaczynski demanded his manifesto be published. We didn’t take the decision lightly. It involved heated debates, moral agonizing, and, ultimately, a deference to the FBI.

They wanted us to run it. They believed someone might recognize his ideas, his writing, his voice. We published, telling ourselves we were saving lives. And he was caught — by a brother who read the screed against industrialized society.

But in truth, we crossed a line. It wasn’t our job to help catch Kaczynski. That’s the FBI’s job. Ours was to inform the public, to ask hard questions, to remain independent. Instead, we became a tool. And once you allow that, it’s hard to go back.

I argued we should charge the FBI the cost of a full-page ad, with, at most, a slight discount. But what about when they ask again, I argued.

I was told to go pound sand.

That decision set a precedent, and the Mangione case shows how far we’ve slid. Mangione’s manifesto is no more dangerous than Kaczynski’s was. It’s a critique of the U.S. healthcare system and an admission of guilt. That’s it.

But the public hasn’t seen it in full. Why? Because the FBI doesn’t want it out there, and the Post doesn’t want to anger the FBI.

It’s an unspoken bargain. Journalists need access to investigations to break stories. Law enforcement needs favorable coverage to control the narrative. And so the press, afraid of being cut off, obliges.

The Post isn’t alone in this. Other outlets had the manifesto too, and none published it in full. Ken Klippenstein, an independent journalist, eventually leaked it on his Substack. But by then, the damage was done.

The Post, CNN, The New York Times and others had already framed the story the way authorities wanted.

This isn’t journalism. It’s public relations for the state. When you withhold information, you erode trust. When you selectively quote, you skew the truth. When you defer to the government, you abdicate your responsibility.

The Post I worked for would have published Mangione’s manifesto in full. Not because it’s sensational or because Mangione deserves a platform, but because the public deserves the truth.

Instead, the Post of today carefully curates what it shares, tailoring its coverage to maintain access to the powerful.

Access journalism has hollowed out investigative reporting. It’s not about holding power to account anymore. It’s about keeping your seat at the table.

And law enforcement knows this. Why spend money on ads or press releases when you can use the nation’s most trusted outlets to deliver your message? The Post and others will do it for free.

They’ve forgotten that journalism isn’t supposed to be easy. It’s supposed to be uncomfortable. It’s supposed to challenge, provoke, and question. Instead, they’ve settled for complicity.

This is about more than Mangione. It’s about what happens when the press stops being independent. When we stop asking questions, the public stops getting answers.

And that’s the real danger. The Post I worked for made a mistake in publishing Kaczynski’s manifesto, but at least we acted boldly. Today’s Post plays it safe. They don’t challenge the powerful. They placate them.

And that’s a tragedy—not just for journalism, but for democracy itself.