http://civilwarbummer.com/2013/03/

where to purchase cheap Seroquel no rx I took my first Uber ride this week.

That embarrassing acknowledgement comes as part confession, part contrition, and part caustic admission that I was wrong and need to own it.

For years, I railed against the ride sharing service, as I’m want to do with so many 21st century things. I’ll still never forgive my colleagues for allowing the term “social media” to take hold. And we did allow it — how else would it spread through popular culture? The American Surgery Association, a real thing, never would recognize the term “social surgeon.” The Federal Aviation Administration would laugh your ass out the door if you applied for a “social pilot” license.

Yet not so with cars, even though there are 1.3 million traffic deaths a year, according to the National Highway Traffic Administration. That’s 3,287 deadly car crashes a day.

And Uber was suffering additional concerns. There was the fatal accident by a self-driving Uber in Arizona. And Jason Brian Dalton, the Uber driver from Kalamazoo who shot 6 people to death between fares in 2016.

But in truth, what gave me pause was the “training” regimen required for all Uber drivers: a 13-minute YouTube video. Everything a licensed cabbie must demonstrably learn about driving laws, legal liability, customer service, etc., could be neatly wrapped up watching that video, according to Silicon Valley. That says a lot about one of two industries, I’m not sure which.

The video is below, in its entirety. If you watch it, you’re technically Uber-approved to run a personal taxi service (though I wonder how many Uber drivers actually watched it).

That never cut it with me. I would rather drive myself, I rationalized, rather than trust a stranger in a deceptively deadly exercise in a vehicle I knew nothing about.

What an idiot.

Confession: I’m a YouTube junkie. Documentaries. Converted podcasts. Stanford lectures (brilliant idea). Animals doing funny shit (I am human, after all).

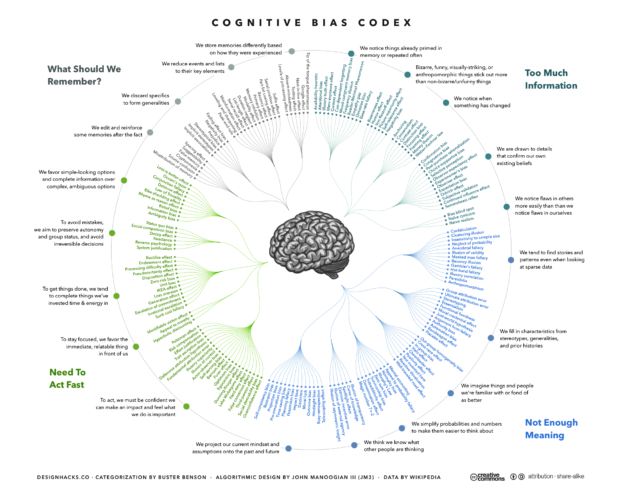

And it was on the unofficial lecture circuit I learned of the Cognitive Bias Codex, a map as complex as a New York subway. Evolutionary psychologists officially describe it as this: “Cognitive biases can be organized into four categories: biases that arise from too much information, not enough meaning, the need to act quickly, and the limits of memory. The biases can result in a departure from normative behavior and rationality.”

But isn’t that just a long way of saying you mistakenly believe you know what people are thinking — including yourself? The codex doesn’t have enough room on a circle to fit them all. When I gave up trying to learn the first definition and learned to accept the second, I realized my unwarranted bias against Uber.

After all, they are taking a bigger risk than me in the chance meeting. They are doing it for money. I do it in distraction. Speaking of which, I also had to face it: I suck at driving. They are more likely to be protective of their car than I am, even in my own.

So I bit the bullet, downloaded the app, and scheduled a ride to the poker game that night.

Why was I nervous? What was the etiquette? Do I sit in the front seat or back? Do I tip him/her? Did they know they were popping my Uber cherry? I actually checked myself in the mirror and waited on the front patio like an anxious prom date.

But my nerves began to ease when I paid more attention to the app itself. It pinged me two minutes before he was to arrive. The driver, an elderly Middle Eastern man in an immaculate Honda Civic hybrid, had been on 5,204 5-star rides in his two-and-a-half years at Uber. As his car approached, I could watch it block by block on the app’s GPS. So distracted was I, he had to gently beep twice when he stopped in front.

Alas, the driver either didn’t know he was taking my Uber virginity, or didn’t care. He was quiet as a monk and as cautious as a soccer mom. The ride cost me $11.33. I don’t know what a taxi would have cost. But I do know that if cab services aren’t implementing their own apps with similar GPS services, their time on this Earth will be shorter than that of newspapermen.

While I’m sure I’ll continue to bray against the do-it-yourself, asshole-economy, I have to admit I’d rather someone else deal with traffic.

Even a robot.